As I mentioned, I’ve been planning to include a “Spitfire mode” into this box. Suddenly a series of intuitive connections have dropped into place.

I’ve been taking a Masters in Arts Education and it’s helped me to see these intuitive insights in new ways. If your main interest is in the “nuts and bolts” of this build, there’s certainly no hard feelings if you want to skip ahead to post #5.

But during this pandemic, I’ve been watching our society struggle with big ideas we’ve largely been fortunate enough to have spent little time dealing with before in our lifetimes. Big, challenging ideas: sacrifice for the greater good; the idea of “what we owe to one another”; the idea of how decent people behave in a crisis.

I’ve been thinking about how much my attitude towards the pandemic was informed by the stories I grew up on from my Mom and Dad. They’d met in WWII London during the Blitz: Dad was a young Canadian who had put on a uniform, picked up a rifle and marched towards the sound of the guns within the first days of September 1939; Mom was just out of her teens, a young Londoner working in a Hawker Hurricane factory.

Deeply embedded in their stories was a tacit assumption that huge, unexpected events sometimes happen, and one day we may be asked to do our part in dealing with them, and it is incumbent upon us to rise to those challenges and sacrifices with as much grace and cheer and determination as we can. That was simply part of my worldview from earliest childhood.

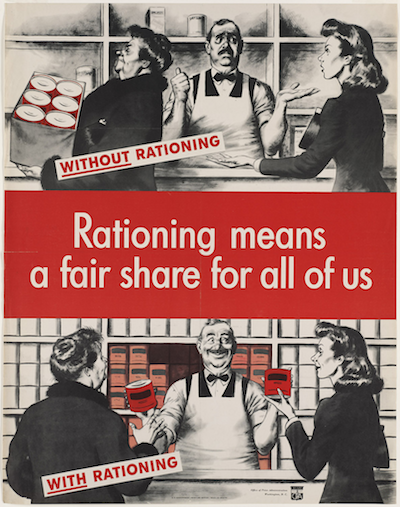

Life in wartime London involved sacrifices that are difficult for us to comprehend today. Britain is an island, and the surrounding waters were infested with U-boats determined to starve it into submission by choking off its food supply. Rationing began almost immediately; petroleum products and fuels in September 1939, food in early 1940. And after the end of the war, the devastation left behind, and the necessity of supporting enormous amounts of refugees in Europe (including the citizens of recently enemy nations) meant rationing would continue until 1953, eight years after the end of World War II. That’s a total of 13 years in which one had to show a ration book and get it stamped. So my uncle Arthur was 10 years old before he ate his first banana (family lore recounts that his initial impressions were quite unfavorable, because he tried to eat it sideways with the peel still on it). To her dying day, my mother scraped every scrap of butter off the foil wrapper before discarding it. Nobody liked food rationing, but pretty much everybody understood why it was necessary.

In those days before GPS and navigational beacons, enemy bomber pilots would use any visual aids they could identify below them to guide them to critical targets for bombing. At night this was the street and house lights that outlined the recognizable shapes of streets that could be correlated with maps. So every house had blackout curtains or shutters and blackout wardens rigorously enforced light discipline at night. It wasn’t that the enemy pilots necessarily bombed the lights of the houses themselves (although that certainly happened, either by error or intention): they used them to guide themselves to juicier targets, so the irresponsible actions of a few would jeopardize countless others. Nobody liked the blackout regulations; everybody understood why they were necessary for the city.

And on so many nights for so many war years, the bomber sorties and the V1 buzz bombs and V2 rockets roared overhead, and the exhausted and vastly outnumbered pilots of the RAF would haul themselves into their fighters to fend them off once more. Those young pilots often joined up for the adrenaline or competitive spirit as much as anything else; that was all swiftly burned off in the brutal crucible of war, the exhaustion of endlessly-repeated sorties. Over time it left them flying beyond exhaustion to the point of “shakes” and hallucination, never knowing what random piece of bad luck that day might leave them victim of an ounce of lead, a burning cockpit, a high-velocity crash, or a two-thousand foot jump via the unreliable parachutes of that time to a hard unforgiving urban landscape. They kept going because they knew there was literally nobody else between the bombs and the streets of their cities; it was up to them, every exhausted grinding day. These young men – mostly between the ages of my own two sons – developed their own language to distance themselves from their fear: nobody “crashed” their “aircraft”, they “pranged” their “kite”; nobody died, they “bought it”, dry military slang for the dreams of soldiers to survive long enough to retire and buy a farm on which they’d peacefully live out their remaining days. They kept going past exhaustion because it was necessary.

Those young men flew both Spitfire and Hurricane fighters. As glamorous as the race-plane derived Spitfires were, the slightly dumpier, workhorse Hurricane fighters my Mom built actually accounted for more overall “kills” than the more elegant Spitfires. This wasn’t because they were technologically superior, but because of the way they were built. The first Hurricanes that were delivered to the RAF – the MKI – were hurried into service with vestiges of World War I biplane technology attached: their wings were built with the same doped linen stretched over plywood-framed wings that you might have found in WWI, and those wings were attached to a steel-tube frame. As a result they were built rapidly and in bulk. Oddly the older steel-tubing construction that offered so little protection was a poor target for enemy bullets, which would punch right through the fabric and out the other side, causing little airframe damage. Like the Spitfires, the Hurricanes were controlled by a stick – part joystick, part steering wheel shaped a bit like an offset letter “D” wrapped in leather for better grip.

I thought about the luxuries I enjoyed, amongst them this hobby making a device tweaked to control Spitfire instruments. I thought of the ideas of “responsibility” and “sacrifice” that had been floating around in my head, and I thought about my Mom and Dad. And I realized it was probably time to listen to the old subconscious, so this is now the Hurricane, for my Mom. This prototype is the MKI, both for its initial rawness and the hint of refinements to come. The IIc that will follow might have a bit more of Canada in it, perhaps made from BC Red Cedar, which will be a good nod to my Dad who had once earned a living for a time as a lumberjack. Like myself, the device would have a bit of both of them in it.

Fun fact: there are Hurricanes are still flying today, over 75 years after WWII. Turns out if you make thing with some care, build it so it’s repairable, and take decent care of it, it might wind up lasting somewhat longer than five years. Who knew?

I didn’t want to do the “kitsch” thing – bogus toy gauges etc – so there are just a couple of quiet nods. But if you see a little echo of that, and if that causes you to stop and muse now and then about what we owe one another, and what sacrifice actually means, and how ours pales in comparison to that of the generations before us, I won’t be displeased. I don’t think my Mom and Dad would be either.